Motives and emotions can penetrate even the most clinical, technical arenas. The root cause of Volkswagen's diesel imbroglio—while digitally embedded in code deep within at least 11 million engine control computers—lies in a far more human pursuit: pride.

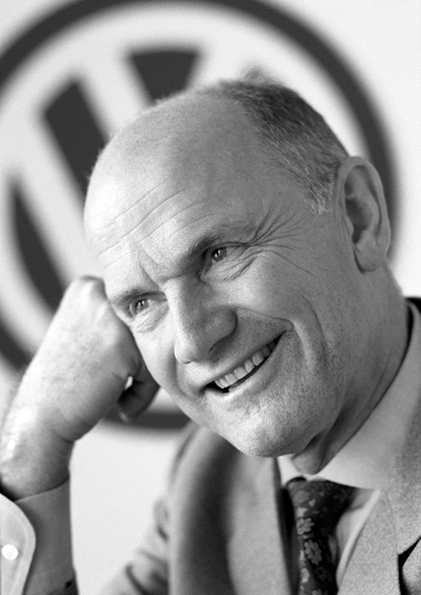

The pride driving remarkable engineering at the Volkswagen Auto Group stretches deep and long. Its most direct link to VW's diesel emissions scandal came in the form of the hyper-efficient "1-Liter" concept car, first shown in 2002 by then-Chairman of the Board and legendary engineer Ferdinand Piech. The 1 Liter's grand purpose was as a technical showcase for the VW's engineering and design. The goal was to deliver staggering fuel efficiency—in this case, 100km from just 1 liter of fuel (282.5 mpg). It required the impossible, and achieving the impossible would make techies, industrial engineers, critics, and even the competition swoon.

Volkswagen believed that calling attention to its own inventiveness with a forward-looking, green, and practical car of astounding efficiency told a compelling story about its technical capabilities, commitment to the environment, and never-ending stretch goals. But it also served another purpose: to brag with subtlety. VW would engineer and show off a car no one else could. We can do this. We will do this. Only VW. Poetically, the 1 Liter concept was carried out in exactly the same manner as the "clean diesel" campaign of smoke and mirrors, with deeply embedded pride and braggadocio, but somehow outwardly subtle.

VW had reason for the pride. Piech is undoubtedly the best engineering mind and product planner in the industry, perhaps ever. He's not just a technical mind, but a political and financial one. He outflanked competitors in 1997 and 1998 to poach Bentley, Bugatti, and Lamborghini for his own VW Group. Piech's résumé is filled with world-beaters and engineering marvels: the Porsche 917 race car, Audi's Quattro all-wheel-drive system and the FIA Rally car that introduced the Quattro name, the 1983 super-aerodynamic Audi 100 (5000 in America) that pioneered flush side glass, the 1000hp Bugatti Veyron, and even dual-clutch transmissions. There have been failures—the ill-conceived VW Phaeton luxury sedan—but he's justifiably a very proud man. Other very proud men came after him, and those men always stood in the dark, unstable shadow of Piech's accomplishments.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...